Anselm Keifer recent work on exhibit at Saint Louis Art Museum | Seen at Large with Chadd Scott

Installation view of ‘Anselm Kiefer Becoming the Sea’ in Saint Louis Art Museum Sculpture Hall. Copyright Anselm Kiefer. Photo by Dan Bradica.

This article was originally published on Forbes.

The Saint Louis Art Museum presents a landmark exhibition for Anselm Kiefer (German; b. 1945) through January 25, 2026. Not simply an exhibition of Anselm Kiefer paintings and sculptures in St. Louis, but an exhibition of Anselm Kiefer St. Louis paintings in St. Louis.

Kiefer, one of the world’s foremost contemporary artists of the past 50 years, first came to St. Louis in 1991. The Saint Louis Art Museum had acquired its second Kiefer artwork, a sculpture, Bruch der Gefäße (Breaking of the Vessels) (1990), and the artist accompanied the artwork to oversee installation. On that visit, Kiefer traveled by boat to the newly constructed Melvin Price Lock and Dam just north of the city on the Mississippi River, past its confluence with the Missouri River.

The experience stuck with him and, decades later, became a subject of renewed interest. Rivers. Rivers and borders. In Germany and America.

“The Rhine, for Anselm Kiefer, has always been a vessel of memory of trauma and destruction and beauty and histories,” Min Jung Kim, the Barbara B. Taylor Director of the Saint Louis Art Museum, told me. “Similarly, with the Mississippi, it sustained for centuries indigenous cultures. It was the backbone of a new nation when the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country. It was the engine of 19th century commerce, and it remains immortalized as a cultural metaphor through song and folklore and literature. (In this exhibition, Kiefer) brings these two important, culturally specific rivers that would normally be divided by continents and seas together in visual dialog in this space, in this scale.”

“This space” is the Saint Louis Art Museum’s soaring Sculpture Hall, cresting at 78-feet and larger on the floor than a basketball court. “This scale,” Kiefer, renowned for the size of his paintings, goes gonzo; four artworks on view in the Hall are 30-feet tall.

The artworks were purpose-painted by Kiefer in response to his time in St. Louis and with the intention of being displayed in SLAM’s Sculpture Hall.

“(Kiefer) came to St Louis again in November of 2023 and we walked the galleries, and at one point we stood up on the (Sculpture Hall) balcony looking down and he said, ‘This is an amazing space,’” Jung Kim remembers.

Her professional relationship with Kiefer goes back more than 30 years. She visited Kiefer in Europe earlier in 2023, hoping to convince him to put a show together for the U.S., and for SLAM to be the host.

“As we were standing up on that balcony, looking down, he said, ‘Min, where could we envision doing an exhibition?’ I said, ‘Anselm, any and or all of these exhibition spaces could be open.’ He said, ‘Well, this space is so amazing. And thinking about the Mississippi and the Rhine, how about if I were to envision doing some work here,’” Jung Kim, who curated the exhibition, continued. “He went back into the studio and immediately started working. Three to four months later, I went to go visit (again) and he had already started working on these two paintings.”

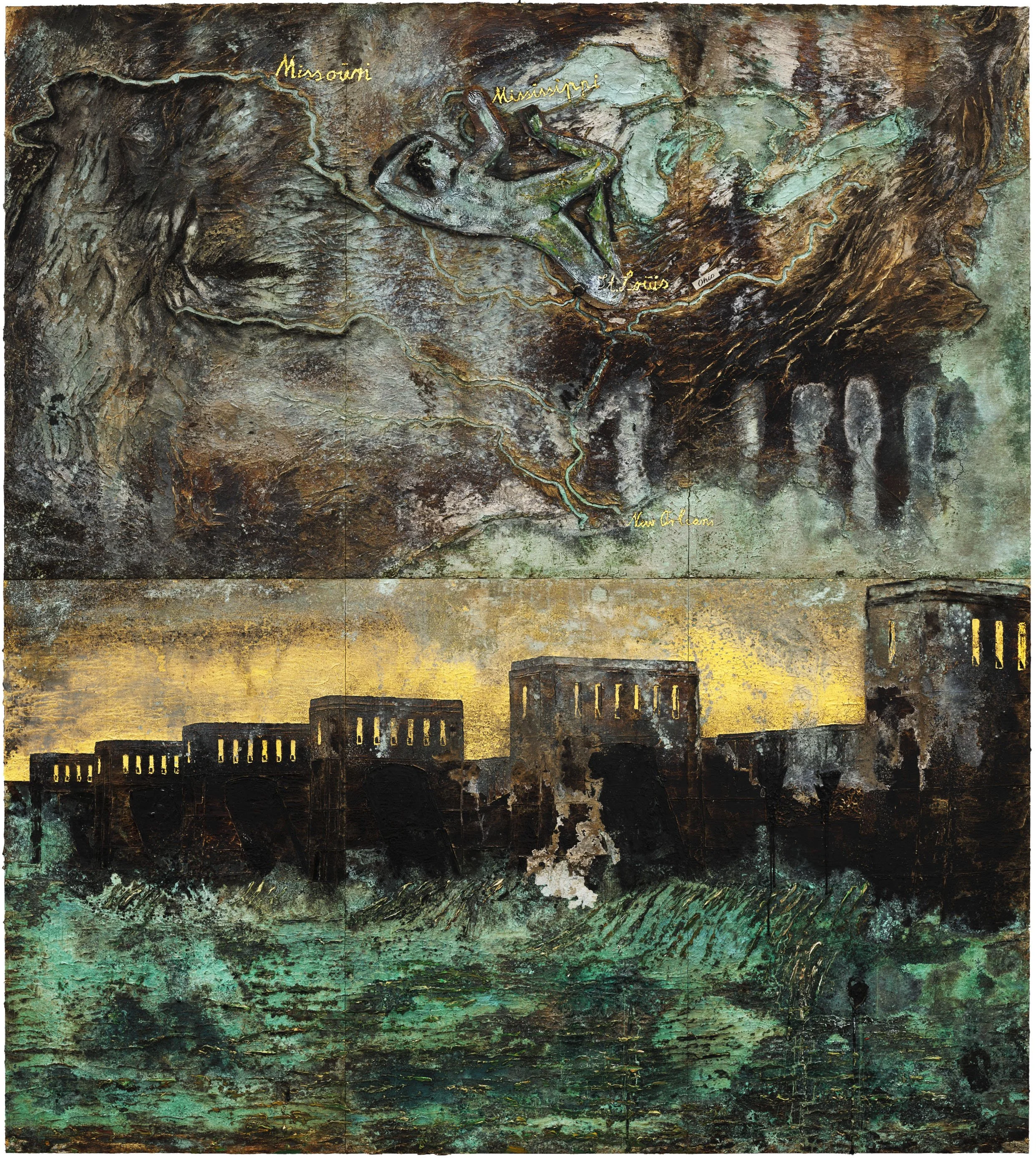

Those two paintings are Missouri, Mississippi (2024) and Lumpeguin, Cigwe, Animiki (2025).

“These two paintings are of the Mississippi River, and as you can see, he has such a vivid memory of that experience, of the Mississippi, the sheer force, the scale, he remembers in this small boat going through these locks and dams, and you see many of these components,” Jung Kim said.

Lumpeguin, Cigwe, Animiki depicts the since-demolished Clark Bridge on the Mississippi River. Its title refers to spirit beings from indigenous Anishinaabe and Wabanaki people. When thinking about the rivers and the Louisiana Purchase and the lands along them, including St. Louis–the Gateway to the West–remember they were purchased from France, but stolen from Native people.

Sculpture Hall continues that legacy.

The building was constructed as part of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. That event was a celebration of the importance of the Mississippi River in the ongoing industrial development of the United States and colonization of the North American continent. It was referred to as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition recognizing the centennial of the purchase/theft. Sculpture Hall was the only building from the Fair designed to be permanent.

Green And Gold

Anselm Kiefer, German, born 1945; ‘Missouri, Mississippi,’ 2024; emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, sediment of electrolysis and collage of canvas on canvas; 30 feet 10 1-16 inches x 27 feet 6 11-16.

Kiefer’s monumental paintings in Sculpture Hall were created with a striking and unusual combination of sediment of electrolysis, verdigris–oxidized copper–gold leaf, metal objects, and oil paint. Gobs of it. The surface of the paintings are layered so heavily in smears of oil paint and so recently completed visitors can smell it. Without any barriers separating guests from the artwork, get close and take a whiff.

“The greens are a relatively new palette. This is where he is so astonishingly innovative,” Jung Kim said. “Sometimes he will use lead, but more often will be using copper, and he will submerge it in a sulfur bath, and then he'll run an electric current through it, and through this electrolysis, it will go through this chemical reaction and process of corrosion, and it will develop this beautiful patina. This verdigris is sometimes used directly–sometimes he'll submerge canvases itself–but oftentimes the corrosion will then sort of settle to the bottom of this bath and he'll collect it, he'll mix it with shellac and paint, and he'll apply it and so you get this really lush tactility and extraordinary color.”

A crusty, metallic, oxidized, crumbling, sea foam green surface color and texture. Fascinating. The surfaces of Kiefer’s paintings double as landscapes themselves. Relief maps.

The artwork for which the exhibition takes its name, “Becoming the Sea,” is centered in Sculpture Hall. It's inscribed “for Gregory Corso,” and includes lines from an unpublished poem by Corso, an American Beat poet.

“’Spirit is life, like a river, unafraid of becoming the sea,’” Jung Kim reads. “It ties in this theme of rivers that was initially inspired by these five monumental paintings in Sculpture Hall, but it becomes a theme throughout the exhibition acting as a metaphor for memory, for transformation, and for the passage of time.”

Kiefer turned 80 this year. He’s a river nearing the end of his path, preparing to enter the sea. Unafraid.

German Art At The Saint Louis Art Museum

Installation view of ‘Anselm Kiefer Becoming the Sea’ in Saint Louis Art Museum Sculpture Hall. Photo by Chadd Scott.

Kiefer hasn’t had a major U.S. museum exhibition in over 20 years. SLAM makes for the ideal location. The institution’s history with the artist goes all the way back to 1983 when it organized “Expressions: New Art from Germany,” a traveling show introducing American audiences to Neo-Expressionism, including works by Kiefer.

In 1987, the museum acquired its first Kiefer painting, Brennstäbe (Fuel Rods) (1984-1987). It is on view in the show which continues beyond Sculpture Hall. Around 40 works from the 1970s to the present, in addition to the monumental, site-specific paintings, can be seen.

Free.

In fabulous Forest Park with extended hours until 9:00 PM on Fridays.

SLAM’s roots are with German art and artists.

The museum possesses one of the largest and most diverse collections of 20th-century German art in the U.S. That collection was jump-started by artist Max Beckmann’s (1884-1950) arrival in St. Louis in 1947 for a teaching position at Washington University.

In 1950, SLAM presented the first exhibition of Beckmann’s work in this country. Following that exhibition, St. Louis-based collector Morton D. May began acquiring Beckmann artworks, building what would become the world’s largest collection of the artist’s paintings.

When May died in 1983, he bequeathed his collection to the museum, further motivating SLAM to prioritize acquisitions of important works by contemporary German artists. Totaling more than 2,500 objects by artists from Germany, Austria and Switzerland, the museum’s holdings include strengths in German Expressionism—including paintings by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Käthe Kollwitz, Paula Modersohn-Becker and Max Pechstein—and postwar German art, including important works by Joseph Beuys, Georg Baselitz, A.R. Penck and Gerhard Richter.

And Kiefer.

As guests walk from or to Sculpture Hall from the rest of the exhibition, they pass directly through SLAM’s gallery hung with Beckmann masterpieces. Connecting with this lineage appealed greatly to Kiefer when thinking about SLAM as a potential exhibition site.

About Chadd Scott

A midlife career crisis at 40 led Chadd Scott to begin writing about art with no background in it following a 20 year career in the sports media. Learning "Art History 101" from YouTube videos, used books, and podcasts, Scott found the more he looked, the more he liked. He now freelances for Forbes.com, Western Art Collector magazine, Native American Art magazine, and Fodors.com among other publications while operating his own website, www.seegreatart.art, a daily look at art exhibitions and events across the United States. Scott's particular interests in the art world are Native American, African American, and female artists and how art intersects with social justice. As he likes to say, "a people's history is best learned through their artwork." Scott especially enjoys traveling to off-the-beaten-path arts destinations across America. His favorite artist is Earl Biss. His favorite arts destination is Santa Fe, NM. Scott lives in Fernandina Beach, FL.